Cigarette smoking leads to poor health-related quality of life and premature death,1 and healthcare professionals can play a key role in facilitating smoking cessation efforts. Even very brief advice from a health care professional increases the likelihood that a smoker will successfully quit smoking.2,3

A review2 of randomized trials involving >31,000 smokers demonstrated that advice from healthcare providers about smoking cessation can help smokers quit. Even if the advice is brief and simple, it increases the likelihood that a smoker will successfully quit and remain a non-smoker 12 months later. Healthcare providers can be much more effective if they act to provide quitting assistance. Indeed, quit rates can be increased 3- to 6-fold with pharmacotherapy and appropriate behavioural support.

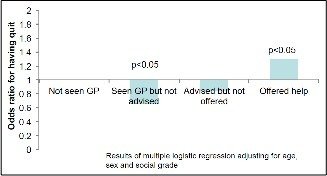

The Toolkit Smoking Study demonstrated that an offer of support by a healthcare professional is linked to successful quitting; in fact, not offering support can reduce the odds of quitting more than if a patient had not seen their healthcare professional at all (Figure 1).4

On the plus side: harm reduction

Despite overwhelming evidence of harm and financial burden, the majority of smokers find it extremely difficult or impossible to quit. From a harm reduction perspective, e-cigarettes reduce exposure to the innumerable carcinogens and toxins found in cigarette smoke.2 An e-cigarette can be a replacement for a conventional cigarette in satisfying the chemical and behavioural aspects of cigarette smoking.

Moreover, in a number of survey, the potential advantages of using e-cigarettes vs. conventional cigarettes included the following:3

- They may make it easier for you to cut down the number of cigarettes smoked, and help people quit altogether

- They may not be as bad for people’s health

- They taste better than conventional cigarettes, and there is no tobacco smoke associated with their use

- They can be used in places where smoking regular cigarettes is banned

- They may provide a viable aid for people who have attempted previous cessation endeavours to quit altogether

With respect to harm reduction, Nutt and colleagues investigated the relative importance of different types of harm related to the use of nicotine-containing products, using a multi-criteria decision analysis model. The authors concluded that cigarettes are the nicotine product causing by far the most harm to users and others in the world today. Attempts to switch to non-combusted sources of nicotine should be encouraged, as the harms from these products are much lower.4

All healthcare providers should identify smokers and offer smoking cessation treatment and behavioural support at every opportunity. If a patient has an issue that is caused or exacerbated by smoking, it is vitally important to discuss smoking cessation.5,6 Interventions may include 1 or more of the following:5

- Brief advice to stop smoking

- Assessing the smoker’s interest in and motivation to quit

- Offering pharmacotherapy where appropriate

- Providing self-help material

- Offering counselling or referral

For people who are motivated to quit, using a combination of counselling and pharmacotherapy is more effective than either alone, and hence, both should be provided to these patients. People who are not ready to quit should know that help is available whenever they are ready.3,6,7 Motivational interviewing can be used to facilitate smoking cessation among patients who are ambivalent or reluctant about changing their use of tobacco.8 Following are the roles that healthcare professionals can play.

Offer Very Brief Advice: The 3As approach

Even Very Brief Advice and an offer of support from the healthcare provider (taking as little as 30 seconds to deliver) can help smokers to quit. A systematic review and meta-analysis3 assessing the effects of opportunistic brief advice to stop smoking together with an offer of assistance found that, compared with no advice to smokers, the likelihood of quitting was 24% higher if the smoker received advice, 68% higher if NRT was offered, and 217% higher if behavioural support was offered. Therefore, very brief advice should be offered to every smoker, and not only to those already motivated to quit.

Very Brief Advice takes just 30 seconds, and is designed to be used opportunistically in almost any consultation with a smoker. The smoker is not asked if he/she wants to quit, because it takes time, may put the person on the defensive, and can be counterproductive. Smokers are also not asked how much they smoke nor are they advised to stop.7 Rather, the smoker is advised that the best way to quit is with a combination of medication and counselling and that the healthcare provider is able to assist the smoker to access these supports if they are interested in trying to quit.

Very Brief Advice involves the “3As:” ASK, ADVISE, and ACT7

- ASK: Ask and record the person’s smoking status.

- ADVISE: Advise the person that the best way to stop smoking is with a combination of medication and support..

- ACT: Take action to provide access to smoking cessation medications and counselling/ behavioural support if the person is interested in trying to quit.

Click here for further information regarding Very Brief Advice and the 3As.

Consider pharmacotherapy

Smoking cessation pharmacotherapies reduce nicotine withdrawal symptoms when smokers are quitting and increase the likelihood they will be able to quit smoking for the long-term. Pharmacotherapy should be offered to all nicotine-dependent smokers who are interested in quitting, unless contraindicated.5 Pharmacotherapeutic options include nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in various forms (e.g. gum, transdermal patch, mouth spray, inhaler and lozenges) and oral medications such as buproprion and varenicline. For more information about NRT, click here.

The importance of counselling

Smoking cessation attempts are associated with a high risk of relapse. The highest risk of relapse occurs within 1–2 weeks of making a quit attempt, and hence adequate support must be provided, particularly during this period. 9,10 Counselling by a variety or combination of delivery formats (self-help, individual, group, helpline, web-based) is effective, and should be used to assist those who express a willingness to quit.5,6,11 Evidence suggests that counselling should be provided on at least 4 occasions for a minimum of 10 minutes per session. Assuming one of the sessions occurs before the quit attempt, follow-up sessions can be scheduled for 1–2 weeks after the initial quit date, and at 4 and 8 weeks, for example.

Counselling should include offers of support and encouragement to build confidence, together with information about the treatment (e.g. how to use the medication correctly, symptoms of nicotine withdrawal, etc.). The person should be advised about strategies to cope with urges and cravings, which may be summarized as follows.12

- Delay: Distract from the urge to smoke by finding something else to do, e.g. talking to someone, going for a walk, or working on a task. An approach referred to as the 4 D’s is often used: Distract, delay, deep breathing, drink water

- Avoid: Reduce or eliminate exposure to people and situations that encourage smoking, or that can reduce the chances of successfully quitting.

- Substitute: Replace cigarettes with something else, e.g. engage in a hobby or some physical activity. For those who feel the need to have something in the mouth, options include chewing gum, or even chewing on a straw. Brushing the teeth several times a day can be another approach, because toothpaste can make cigarettes taste unpleasant.

For smokers unable/unwilling to completely quit smoking, reducing the number of cigarettes smoked has been proposed as a possible option. Pharmacotherapy may be started to help the patient cut down the amount smoked, as a staged approach to smoking cessation. However, although reduction in heavy smoking (≥15 cigarettes/day) can reduce the risk of lung cancer, it does not decrease the risk of myocardial infarction, hospitalization for COPD, or all-cause mortality compared with heavy smokers who do not change smoking habits. Therefore, reduction may be considered a temporary measure for smokers who are not ready for complete cessation, and may be helpful for heavy smokers to achieve a level where quitting is more likely.5,13

Addressing nicotine withdrawal

Nicotine withdrawal may be associated with symptoms such as dysphoric or depressed mood, insomnia, irritability, frustration/anger, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, and increased appetite or weight gain. Patients should be advised that this discomfort is temporary. Suggestions for managing these symptoms are provided in Table 1. 14

Table 1. Counselling regarding withdrawal symptoms14

| Symptom | Advice for patient |

|---|---|

| Tenseness, irritability | Go for a walk. Take deep breaths. Soak in a warm bath. Meditate. |

| Depression | Use positive self-talk. Speak to a friend or family member. Seek medical advice if the depression is intense or does not abate. |

| Headaches | Use mild analgesics. Drink plenty of water. Relax and rest. |

| Appetite changes | Follow a well-balanced diet. Choose healthy, low-fat snacks such as fruit or vegetables. |

| Constipation, flatulence | Drink plenty of fluids. Eat lots of fruits, vegetables and high-fibre cereal. |

| Insomnia | Avoid caffeine-containing beverages (e.g. coffee, tea, cola), particularly before bed. Try relaxation exercises before bed. |

| Difficulty concentrating | Break large projects into smaller tasks. Take regular breaks. |

| Cough, dry throat and mouth, nasal drip | Drink plenty of fluids. |

| Dizziness | Sit down and rest until it passes. |

Addressing relapses

Unsuccessful quit attempts should not be viewed as failures, but rather as learning experiences. Smokers who have unsuccessfully tried to quit should be reminded that most people make repeated quit attempts before they are successful. The circumstances of the relapse should be reviewed, and new strategies, including alternative/additional pharmacotherapy, should be tried.9 It is important to discuss relapses in a non-judgmental way and it is a method to move the patient along the quit continuum.

Becoming a Certified Tobacco Educator

For those clinicians who are interested, the Certified Tobacco Educator (CTE) credential recognizes healthcare professionals who provide tobacco prevention and cessation services to their patients.15 This new credential demonstrates to your patients, peers and supervisors that you have the competencies to provide comprehensive, evidence-informed care in tobacco. The credential is based on 2 sets of competencies:

- Foundational Health Education Competencies

- Tobacco Education Competencies

The requirements for taking the CTE examination are threefold:

- You must have a degree or diploma in a recognized healthcare profession that includes counselling within its scope of practice.

- You must complete an accredited health education program. Such programs are offered in various locations across the country.

- You must complete a following tobacco education programs. Such programs are offered in various locations across the country.

For further information on the Certified Tobacco Educator Program, click here.

Conclusions

Nicotine addiction is a major factor underlying smoking behaviour. Most smokers indicate that they wish to quit, and even brief advice from a healthcare provider can increase the likelihood that they will to so successfully. Very Brief Advice takes as little as 30 seconds to deliver, and can be used opportunistically in almost any consultation with a smoker. Smokers are offered support for smoking cessation, not education. The best way to ensure that people quit is through a combination of medication and behavioural support; pharmacotherapy options include nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion, and varenicline. Counselling by a variety or combination of delivery formats is effective, and should be used to assist patients to quit.

References

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519.

- Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, et al. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;5:CD000165.

- Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A, et al. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction. 2012;107(6):1066-1073.

- Smoking in England website. Smoking Toolkit Study. Available at: http://www.smokinginengland.info/. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- Supporting smoking cessation: a guide for health professionals. Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2011. [Updated July 2014]. Available at: http://www.racgp.org.au/your-practice/guidelines/smoking-cessation/. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- CAN-ADAPTT Canadian Smoking Cessation Clinical Practice Guideline. Available at: http://www.nicotinedependenceclinic.com/English/CANADAPTT/Guideline/Introduction.aspx. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- Very Brief Advice Training Module. National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training. Available at: http://www.ncsct.co.uk/publication_very-brief-advice.php. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- Herie M, Selby P. Getting beyond ‘Now is not a good time to quit smoking:’ Increasing motivation to stop smoking. Smoking Cessation Rounds. 2007;1(2). Available from: http://ottawamodel.ottawaheart.ca/sites/ottawamodel.ottawaheart.ca/files/omsc/docs/3.increasingmotivationtostopsmoking.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- Smoking cessation. Available at: http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/411/follow-up.html. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99(1):29-38.

- Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/index.html. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- So You want to Stop Smoking? Available at: http://www.jarrete.qc.ca/en/fiches/Tips_to_stop_smoking.html. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ. The feasibility of smoking reduction: an update. Addiction. 2005;100(8):1074-1089.

- Smoking Cessation Guidelines: How to Treat your Client’s Tobacco Addiction. Available at: http://www.smoke-free.ca/pdf_1/smoking_guide_en.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- Canadian Network for Respiratory Care website. Certified Tobacco Educator Program. Available at: http://cnrchome.net/certifiedtobaccoeducators(cte).html. Accessed September 22, 2016.